George Harrison’s obscure and weird album, which you’ve probably never heard.

Solo album and strangest

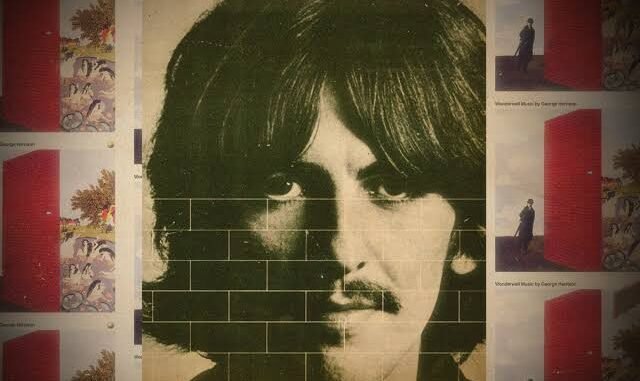

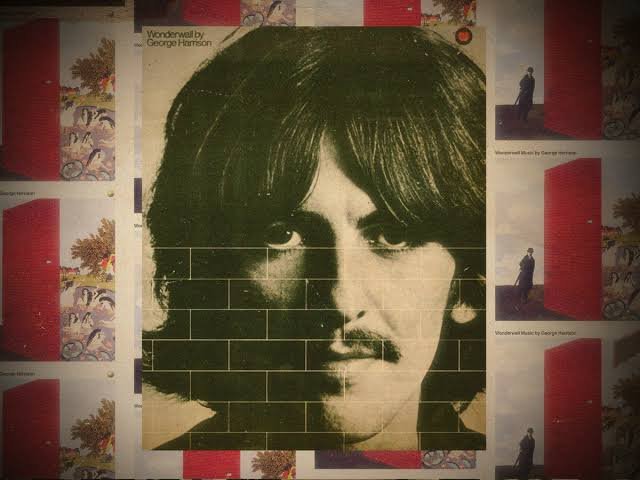

George Harrison’s ‘Wonderwall Music’: the Beatles’ first solo album and the strangest one too.

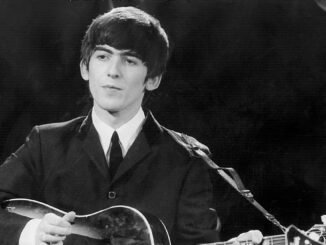

George Harrison’s exotic music to Joe Massot’s swinging sixties cinematic head trip film Wonderwall was the first solo Beatle project, unless you count Paul McCartney’s 1966 soundtrack to The Family Way, which was credited to The George Martin Orchestra. Wonderwall Music, released in 1968, is a delightfully diverse collection of songs that range from traditional Indian ragas to cheery nostalgic-sounding pieces to proto-metal guitar freakouts. It’s a minor classic that I wish more people knew about. I’ve been a huge fan of this album for a long time, placing tracks on mixed CDs and tapes. Even die-hard Beatles fans have often overlooked Wonderwall Music. It’s a real hidden gem.

Harrison’s primary collaborator on the Wonderwall soundtrack was orchestral arranger John Barham, who transcribed Harrison’s “western” melodies into a musical style that Indian musicians in Bombay could use. Barham was a student and worked with Indian sitarist Ravi Shankar, who introduced him to the quiet Beatles. Barham, who would later create the music for Alejandro Jodorowsky’s psychedelic western El Topo and contribute to Harrison’s All Things Must Pass, played piano, harmonium, and flugelhorn and served as orchestral arranger on several tracks.

Solo album and strangest

Harrison subsequently explained that Wonderwall Music was “partly an excuse for a musical anthology to help spread the word,” and that he chose instruments that were not as familiar to western people as they are now, such as shehnais, santoor, sarod, surbahars, tabla tarangs.

Harrison recorded the “English” portion of Wonderwall Music in December 1967 with Barham, Ringo Starr (using the alias “Richie Snare”), and Eric Clapton (here credited as “Eddie Clayton”), as well as several session players and the Remo Four, a Liverpool band. The Indian classical performers were recorded the next month in Bombay. “We recorded backing tracks to accompany certain points in the film,” Remo Four drummer Roy Dyke subsequently stated of the album. “George timed everything with a stopwatch: ‘We need one minute and 35 seconds with a country and western feel.'” Alternatively, ‘We need a rock thing for exactly two minutes.’ Nothing was actually written.We’d talk over ideas he wanted, play something, and he’d say, ‘That’s good, keep that. I like the piano there.’ It was very experimental. The idea was to set an atmosphere.”

Peter Tork of the Monkees also played an uncredited banjo part that was utilised for a cue in the film, but not on the record. It was released on November 1st, 1968, a few weeks before the White Album, and was Apple Records’ debut release. It’s probably not too farfetched to call it the first “world music” endeavour by a big rock performer. If not the first, it is surely one of the first of its kind.But Wonderwall Music is far too unique to be classified as a global music album. Some of it sounds like the New Vaudeville Band after they’ve consumed a lot of coffee. Some of it sounds, predictably, like psychedelic instrumental Beatles outtakes.

There are several fantastic tracks on Wonderwall Music, but the one I want to highlight first is ‘Ski-ing’, a two-minute sonic screamer in which Eric Clapton and Harrison create the blueprint for the Buttlhole Surfers’ guitar sound when Paul Leary was a child.

On reflection, Harrison’s Wonderwall Music is one of those albums that fell through the cracks not because it was bad, but because it just didn’t fit the story. Too strange to belong in the Beatles canon, too whimsical to be taken seriously by the prog crowd, and much too stoned-sounding to ever make an appearance on classic rock radio. That is precisely why it is worth your time. George is at his most exploratory, pulling at loose melodic strands to see what happens, and sometimes falling into entirely new areas. Ignore the Beatles trainspotters, who regard it as an embarrassing quirk.It’s a bizarre, lovely, imperfect little beast, the kind of record that makes you wish more megastars had the bravery to break the rules and have some fun in the studio.

Be the first to comment